Pubblicato il 16 Gennaio 2026

Walking on the Via Francigena. Identity and Connections of a Cultural Route

di Leonardo Porcelloni

Historic routes are not inert ruins. They remain devices that shape space, relationships and practices, with consequences for mobility, landscapes and local governance that are clearly visible in their contemporary practice of walking. Among historic cultural itineraries, the Via Francigena is one of these living organisms: it was born as a medieval weave of paths and, over time, becomes a cultural landscape, a travel experience, and heritage governance. Looking closely means observing how contemporary societies rewrite mobility and the very meaning of places.

The monographic volume From Historical Mobilities to European Cultural Routes. Via Francigena, Heritage, and Pilgrimage (FrancoAngeli, 2025) intertwines historical, geographical and ethnographic viewpoints. It does not separate yesterday and today; it makes them speak to one another. Routes do not end with a given era. They change function, words and audiences. Yet they remain devices that order space, create connections and produce identities. For centuries the Francigena has been, and continues to be, a network, a road-territory. The image of a “line” is a slippery conceptual shortcut. In reality the route is polysemic: it links and separates, opens and selects. Today, when it is reproposed as a cultural and tourist itinerary, the risk is to oversimplify it. The necessary task is the opposite: to recognise stratifications, variants and discontinuities, and to translate them into an experience that is legible without flattening them.

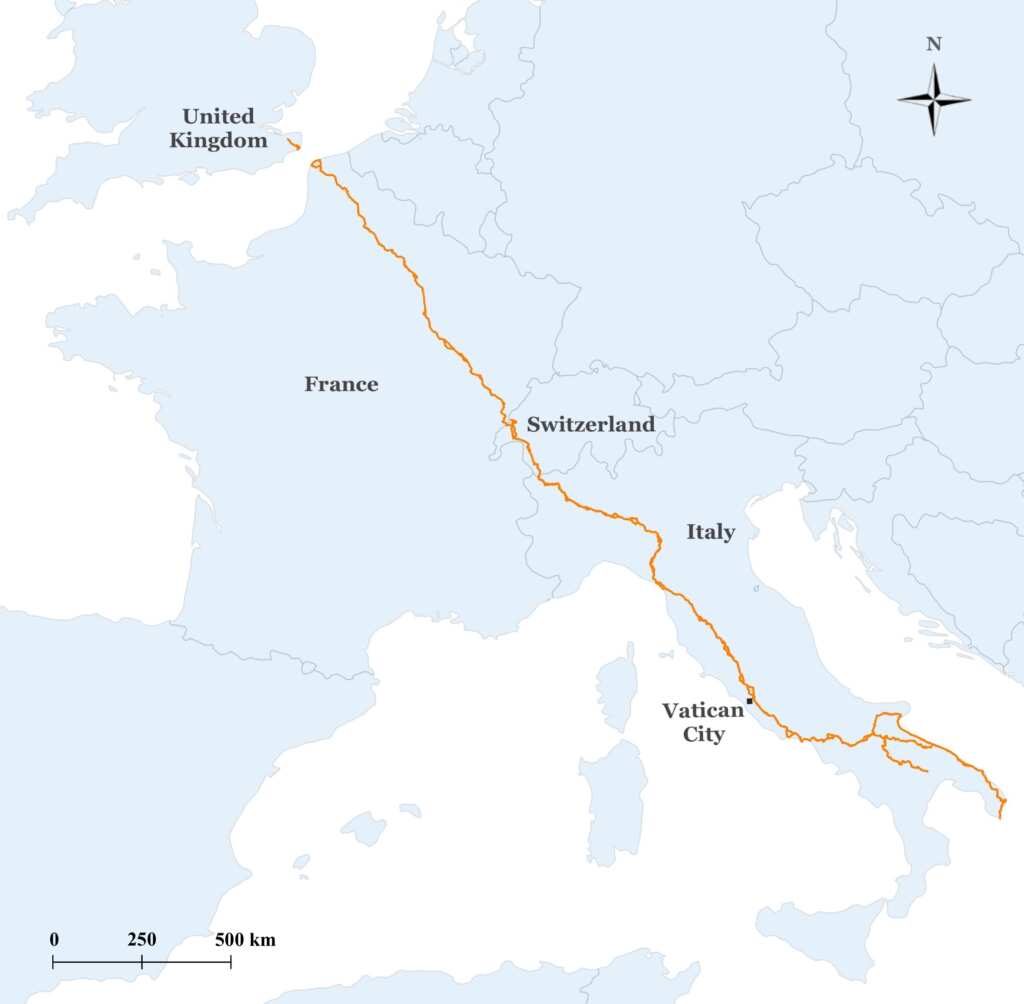

Current route of the Via Francigena as identified by the European Association of the Via Francigena Ways (author’s elaboration).

This is where the Council of Europe’s Cultural Routes Programme comes into play. It is a framework that promotes thematic networks and cooperation between territories, bringing research, enhancement and public use into dialogue. In the case of the Francigena, this framework has supported the transition from historical archive to landscape in motion with a transnational horizon: not only a footpath to be travelled, but a platform that includes hospitality, narratives, waymarking and governance.

Accordingly, telling the story of a route requires multiple scales of analysis. The European scale helps to grasp the longue durée, the evolution of road networks and cultural exchanges. The local scale brings out the details: bridges, fords, hospices, shrines, mule tracks, church towers that functioned as landmarks. Here a micro-territorial approach becomes decisive. It maps traces, checks continuities and changes, listens to inhabitants, observes how places are used.

The study of contemporary use of the route, based on questionnaires, interviews and ethnographic methods, records practices, perceptions, forms of travel and the dynamics between walkers and communities. This empirical corpus lends weight to the question of what makes a historic route operative today. The answer does not lie in the physical line alone, but in the processes of identifying and including heritage and in the set of relationships that the territory sets in motion. From the perspective of historical mobility, these dynamics have been brought into focus through geohistorical documentation, fieldwork, and cartographic elaborations made dynamic by spatial analyses.

Walking imposes a sequence. The world appears in stages, with rhythms different from those to which we are accustomed. It is a bodily experience and, for that very reason, a cognitive one. Walking reorganises attention, brings primary needs to the fore and resets life’s priorities, makes gradients palpable and restores its own sense of time. It is also a symbolic gesture. Today religious pilgrimage and secular travel share many motivations: search for meaning, wellbeing, contact with nature, desire for sharing and community. The identities of walkers are porous; the pilgrim/tourist dichotomy is a simplification. Practices and infrastructures of use overlap, while motivations and the inner journey differ, translating into different ways of engaging with the itinerary and heritage.

“Pilgrim’s Garden”, La Vecchia Posta Hostel (Gallina, Siena). Photo by the author.

For hosts, this overlap is crucial. It influences how hospitality is organised, how rules are communicated, how expectations are shaped. In donation-based accommodation, for example, conviviality and attentive listening matter. In many cases, what initially appears to be an ephemeral sociality, since the pilgrim often arrives in the late afternoon and leaves at dawn the following day, produces communitas that leaves traces. It is a resource, but it requires care.

Here governance choices carry weight. A functioning network sets minimum standards, supports less equipped territories, coordinates communication, measures impacts, invests in training. And it holds together themes often treated separately: protection of assets, quality of hospitality, accessibility for all, environmental sustainability, maintenance of waymarking, safety. The point is not only to have more walkers, but to build a quality landscape in which the route becomes an opportunity to rethink services, connections and local economies. There is therefore a less visible tension between linearity and territory. To privilege the itinerary as a simple link between departure and arrival is limiting. It is the weave of relationships that gives quality to the route, including lateral traces, villages and forgotten places that need to be researched and integrated.

Spatial analyses bring out territorial patterns and the interactions between mobility practices, infrastructures, heritage and the evolution of landscapes. To speak of heritage along a route means to recognise a process that goes from selection to recognition, from study to restitution and finally to public use. This process varies according to the actors involved, the knowledge available and the sensibilities of the time. The inclusion of new segments, the rediscovery of neglected areas and the attention to intangible testimonies are choices that set the course ahead. In this framework, nomination to UNESCO World Heritage is not an automatic goal, but an exercise in coherence: it requires a robust narrative, well-argued boundaries and management capable of sustaining them. The label does not replace substance; it makes it more demanding. The quality of an itinerary is measured by its capacity to bring out and connect the local systems that the route ties back together.

The Francigena also lives in the realm of imagination. Photographs, diaries, social media, credentials and stamps construct a repertoire of signs that fuels the desire to set out. This is not a detail. The imaginary guides behaviours, selects places, creates seasonality, generates expectations. Working on this plane means narrating the route with measure, respecting the limits of fragile rural contexts and historic centres. It means distributing flows, proposing slower timings, giving value to the off-season, avoiding the saturation of the most famous points. Narrative can educate. It can teach people to dwell, not only to pass through.

Today, pilgrimage remains a powerful form of mobility and of engaging with place. It may be religious or secular, but it is almost always transformative (liminoid). Walking for days deconstructs routines and roles. It suspends haste. Many return to their own steps and repeat stretches already travelled. This “after”, still little studied, is crucial: what remains of a route when one returns home. How does the relationship with everyday places change. Which practices are carried back. Investigating post-pilgrimage trajectories makes it possible to grasp more clearly the cultural and psychological impact of slow movement, situating it within the framework of continuous mobility: a contemporary response to an archetypal need for movement that runs across societies.

Pilgrims passing through Vignoni Alto (Siena). Photo by the author.

It is necessary to hold differences together: from the Alps to villages, from the coast to major urban centres, from hilly countryside to woods. The network works when these differences enter into dialogue and the route operates as a common grammar that recognises local specificities. It is a geography made at walking pace. If there is a synthesis, it is that of care: care for historical traces, so that they are not lost; care for those who travel, so that they find hospitality and meaning; care for resident communities, so that they remain protagonists; care for the language with which we tell the route, so that it does not lapse into a slogan but guides informed choices.

When ancient routes come back into practice, they do not ask to have their past replicated; they invite us to make them laboratories of the future. Walking thus takes on both a civic and a cultural value: it builds networks of responsibility and restores depth to our gaze on territories. In this framework, the Francigena represents a significant European test within the Council of Europe’s Cultural Routes Programme, showing that mobility can be a common good capable of producing synergies and new territorial narratives in motion.

Leonardo Porcelloni

Opening image: Romanesque bridge, Groppodalosio (Massa-Carrara). Photo by the author.

Rivista di Antropologia Culturale, Etnografia e Sociologia dal 2011 – Appunti critici & costruttivi